Click here for a full transcript

Lyme disease does a lot of things inside and to the body. But Lyme disease is part of a much larger ecosystem, and we now have the tools to alter that ecosystem - permanently.

Blacklegged ticks are not typically born carrying Lyme disease. They have to get it from something, and typically, they get it from feeding on a mouse during their very first blood meal.

(Sara Plourde, NHPR)

Think of it this way: mice are like mobile Lyme disease storage tanks scattered all over the forest floor. The ticks are delivery trucks carting around the bacteria, dumping it into empty storage tanks, and filling up from other ones along the way.

There are, roughly speaking, three main ingredients in the Lyme ecosystem: ticks, mice, and deer. But deer are what scientists call incompentent reservoirs, which means they don’t actually get infected with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease.

So if mice are storage tanks, and ticks are delivery trucks, the deer are more like the delivery truck factories because adult ticks literally reproduce on top of them, before dropping off to lay their eggs.

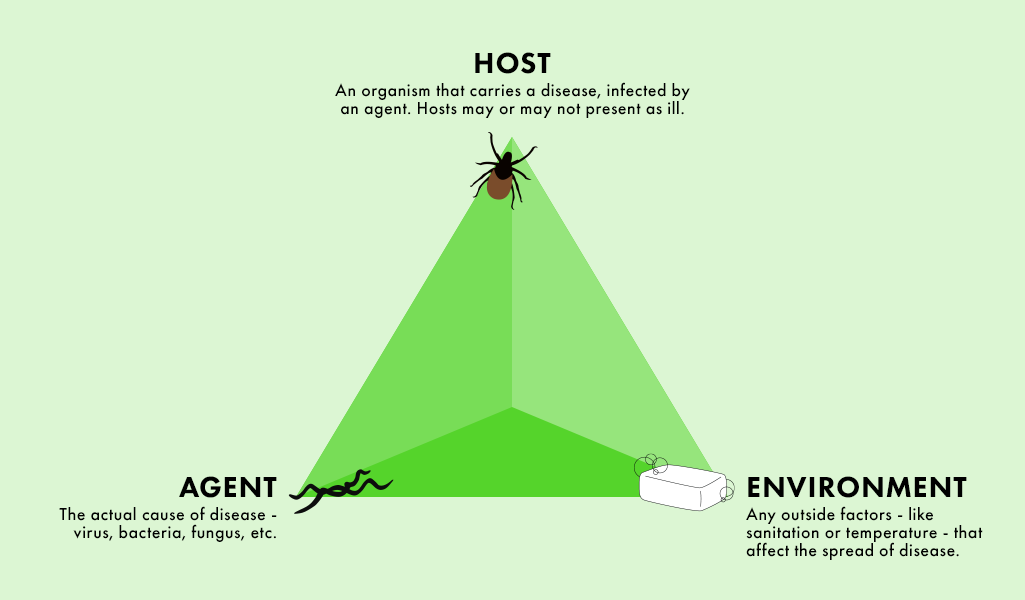

Gross as all these details may be, they present an opportunity. If all three of these are required to spread Lyme, that gives three potential avenues to interrupt the cycle and spread of the disease. Why not just remove one of the ingredients and see what happens?

Off the coast of Maine, Monhegan Island had an overabundance of deer and an abundance of ticks. So, in the 1990s, a proposal was made - to change the makeup of the island permanently by killing deer. The villagers hired a sharpshooter to do the job. They killed 72 that first winter; 35 the next year. For some reason, the number of ticks actually went up. And then, a final vote among residents: 31 to 23 in favor of complete eradication. The last 6 deer were killed in 1999. And a few years later, no infected ticks. It worked.

Biocontrol isn’t usually as clear cut as it was on Monhegan island - here’s just a handful of factors that can influence the tick population and spread of Lyme. Other factors, like the biodiversity of a specific location, can have a huge influence on how well any of these would work. (Sara Plourde, NHPR)

Islands are amazing places to do research because they are contained. The ocean is a natural border that limits the number of factors that can influence an experiment. So, if you want to see how change ripples through an environment, you’re more likely to see a direct cause and effect in an island ecosystem. You can introduce an element here, or take something away there and see what happens.

Nantucket is one of the worst affected areas for Lyme disease in the country. The island, located off Cape Cod in Massachusetts, is covered in beaches and salt marshes scrub oak and pine barrens, and tall grasses. But despite the beauty, it’s not actually quite as biologically diverse as the mainland. There are fewer species of plants, fewer species of animals.

Even though Nantucket is small, it’s many times the size of Monhegan and home to thousands of deer. Efforts to even cull the herd have been controversial so not only would it be logistically more difficult to eradicate them all, it’s politically unfeasible.

But there are two other organisms in the trifecta: two more opportunities to stop the cycle. Killing all the ticks is impossible for logistical reasons, which leaves mice. Scientists at MIT have come up with an idea to immunize the mice, a project called Mice Against Ticks. The plan would alter the genes of mice to block transmission of Lyme. Thousands of these modified mice would then be released onto the island.

But some of the very things that make islands wonderful places for research - fewer variables, fewer complications - are also drawbacks when applying these lessons to a mainland ecosystem with a dizzying number of variables.

Biodiversity is a huge part of whether and how Lyme rates increase and decrease in a given area, and it is just hard to measure. Lyme rates - in people - have been going up steadily since it was first discovered - but if you look year to year, there are booms and busts.

(Sara Plourde, NHPR)

Remember way back to episode 1 and the epidemiological triangle? The third point was the environment. And in the case of the Lyme epidemic, it’s the point that we have been unintentionally sharpening for hundreds of years.

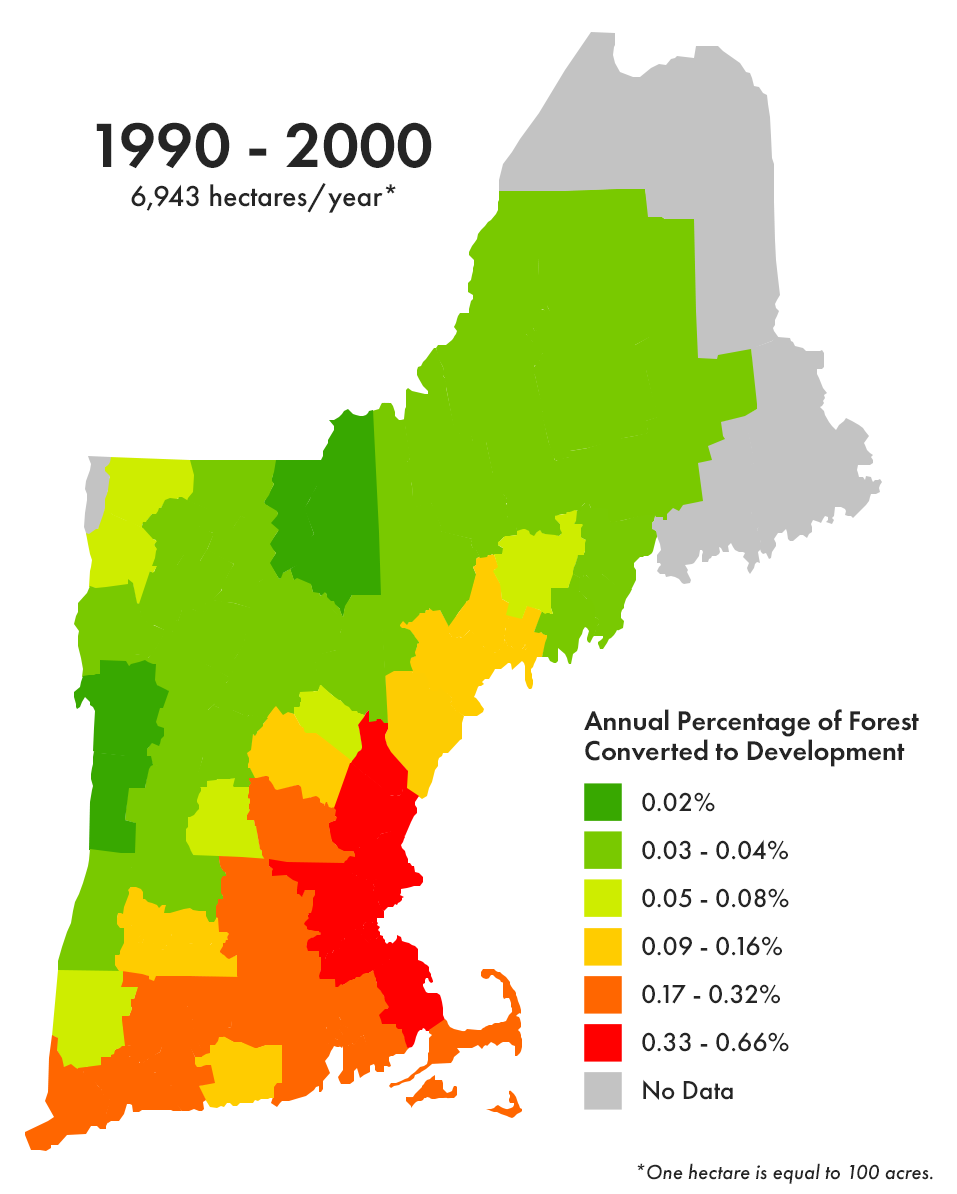

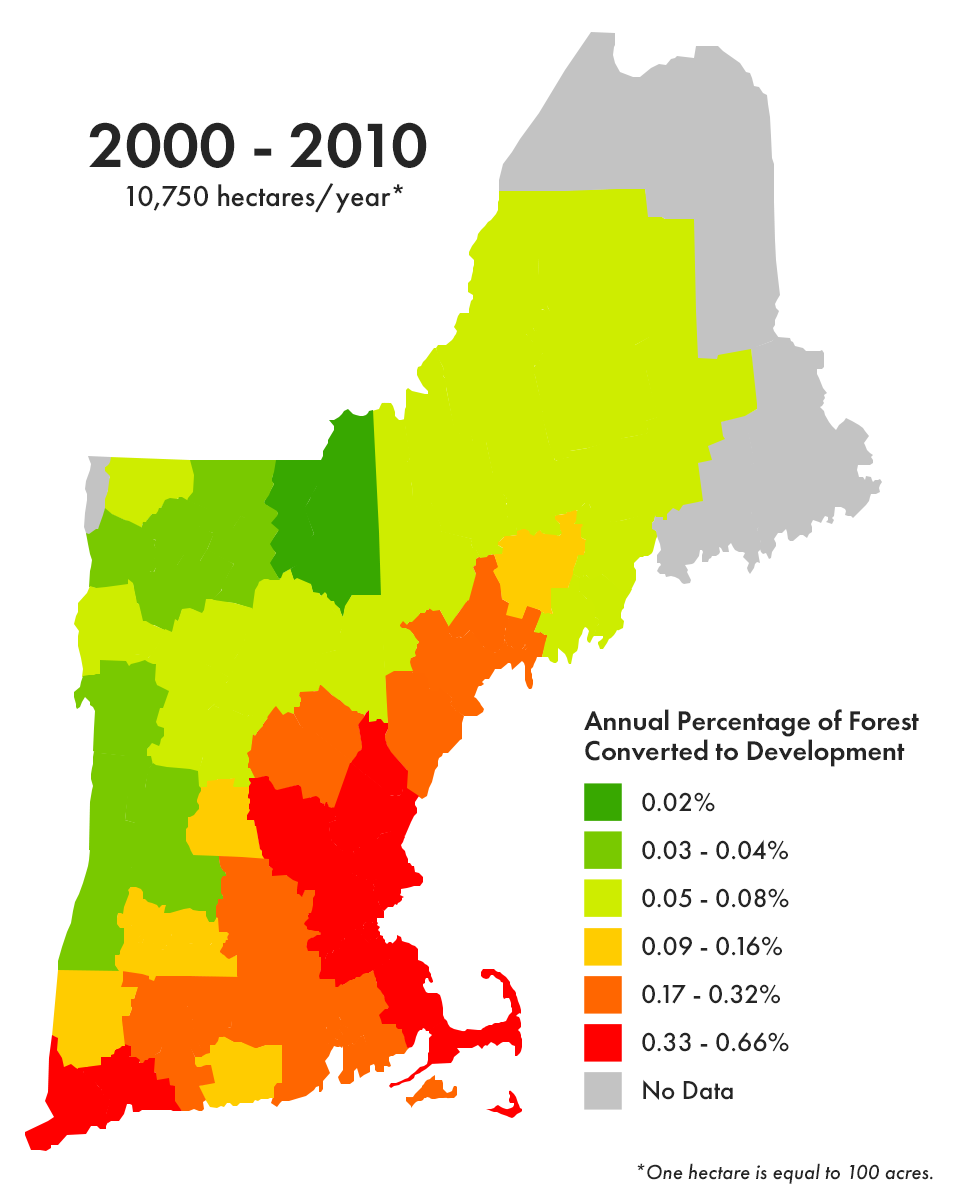

From housing and transportation, to white flight and agriculture, a dizzying number of cultural factors have led us to maximize the number of deer : more than 30 million in America today. We’ve built homes and roads, cutting back into forests. Our communities leapfrog across natural areas and slice odd shapes into the landscape, fragmenting forests in a way that pushes away predators and increases the amount of forest edge next to homes. The edges of forests are where mice do best. In many ways, the risk of getting Lyme disease is higher in your yard than in remote parts of the Appalachian Trail.

Increasing development & deforestation means we are living closer to forest edges - along with mice and ticks. (Sara Plourde, NHPR)

This is the stage that was set for Lyme disease in 1975, when Polly Murray’s kids were out playing in the woods of Lyme, Connecticut.

Wherever the hosts go, the ticks go. But historically, that hasn’t always meant they’d survive. Previously, if a bird deposited a tick too far north, or it fell off on a beach or in a bog, the tick’s journey would come to an untimely end.

Different ticks prefer different environments but generally, they don’t like it too cold and they don’t like it too dry.

Because now, with global temperatures going up and many areas experiencing wetter weather, the ticks have more places to gain a foothold and survive the journey. This and other factors aren’t just spreading Lyme disease but are helping to spread all sorts of tick-borne pathogens. Some of these are very much like Lyme disease and others are more rare but more deadly.

In the forty plus years since Lyme disease was first recognized and named, we have learned so much about spirochetes, inflammation, symptoms, and society. But the best technology currently available for stopping ticks remains socks and pants.

Above: Images from Taylor’s reporting trip to Nantucket, MA (Justine Paradis, NHPR)