Click here for a full transcript

Here’s a simple question with a really complicated answer. How do you know if you have Lyme disease? Not how do you know if you’ve ever had it, but how do you know the bacteria is in your body… right… now?

The way different doctors answer that one question might be the single greatest contributor to the existence of Lymeworld.

Todd Murray pictured at a home he is renovating in Massachusetts, where he sat for an interview. (Taylor Quimby, NHPR)

Toward the end of 1994, Dr. Allen Steere, along with scientists from the CDC and other government agencies, met in Dearborn, Michigan to address a serious problem that had cropped up with the Lyme disease laboratory tests: namely, that they were terrible.

The first diagnostic tests for Lyme came out in the 1980s but the tests weren't standardized. Some of the tests used to diagnose Lyme disease are read visually - as in, a technician literally looks at a sample and interprets whether it’s positive. Depending on the person reading the slide, one might call it negative while another person might call it positive. Lyme antibodies can also look like antibodies for other diseases.

For these reasons, among others, people back in the 1980s and 1990s didn’t trust the tests - and studies showed that they had good reasons.

So the scientists who convened in Dearborn, Michigan, in 1994 sought to give Lyme testing uniformity, to agree, in essence, on what to call positive and what to call negative.

The approach was called the Dearborn Criteria, but a standardized approach didn’t put questions about testing to bed. Partly because the criteria, while more accurate, is confusing to patients because it’s two-tiered: meaning there are two tests used to get a positive diagnosis.

But also, the tests are not good in the first few weeks of an infection. Early on in an infection, patients haven’t yet developed antibodies for Lyme disease yet so results will come back negative. That’s alarming because a lot can happen in the first few weeks of Lyme disease.

The Dearborn Criteria was also more conservative about who tested positive, and that left a lot of patients feeling like the rug had been pulled out from under them.

After the meeting in Michigan, demand for alternative testing grew. And this is maybe the biggest reasons that the Dearborn meeting failed to solve the testing problem: labs don’t have to use it. A handful of labs have continued to use tests that aren’t endorsed by the CDC.

What most of these alternative tests do is run the same tests, but interpret the results differently. They move the cut-off point for what’s considered positive.

For the droves of people who get diagnosed and treated quickly, Lyme disease can be no big deal. But for those who don’t, Lyme can transform lives in dramatic ways, and cause a variety of nasty symptoms. In very rare cases, it can even end in death.

Do you have Lyme disease, or don’t you?

An algorithm for determining whether a subject is positive for Lyme/Lyme antibodies (Source: “The Past, Present, and (Possible) Future of Serologic Testing for Lyme Disease,” Elitza S. Theel, Mayo Clinic)

Diseases do not always appear the way they do in medical textbooks. Instead, they appear on a bell curve. Most people who get Lyme disease are in the center of the bell. Those on the left are patients who for some reason don’t get very sick. Those on the right are the patients that get much, much sicker.

In the days after a tick bite, the Lyme disease pathogen can slowly make its way from your skin into your bloodstream. From there, it can hitchhike through your circulatory system and get into all sorts of bad places.

It can wind up back in your skin and cause multiple rashes all over your body. It can wind up in your joints and cause pain and swelling. It can wind up in your nerves and cause tingling, pain, numbness, or weakness in the arms and legs, or even Bell’s Palsy

(Sara Plourde, NHPR)

If the Lyme pathogen snakes its way into your skull, it can cause inflammation in the meninges. That’s the area surrounding your brain, and swelling there can cause excruciating head and neck pain. Less than 2% of confirmed cases between 2001 and 2015 reported meningitis.

Even further on the bell curve are symptoms associated with sight. Lyme can burrow inside the optic nerve, and Inflammation there can cause double vision, or in very rare cases, blindness.

And most notably, Lyme can squeeze in between the cardiac tissues in your heart and slow the electrical signal that makes it beat correctly. Making up just 1% of confirmed US Lyme cases between 2001 and 2015, it’s a rare complication of Lyme but it is the one that can kill you.

Since 1985, the CDC has tracked nine deaths in the medical literature to heart infections associated with Lyme disease. This complication is called Lyme Carditis, and people who get it are less likely to have gotten a bull’s eye rash.

Rare as they are, symptoms like Bell’s Palsy and Lyme Carditis share an important quality: they can be measured using tools and tests like an echocardiogram or physical examination.

Part of what makes these symptoms so frightening is that they seem disconnected but there is one thing that pretty much unites them all: inflammation. In Lyme disease, the symptoms are caused by your own immune system as it attempts to hunt down and fight off the invaders.

Inflammation might also be the key to one of the biggest mysteries in Lyme disease: Post-Treatment Lyme Syndrome.

Post-Treatment Lyme Syndrome describes the 10 to 20% of Lyme patients that continue to have symptoms after treatment. It’s characterized by hard to measure symptoms like fatigue, general muscle and joint pain, and depression that can have a huge impact on your quality of life. It’s a condition that can take months or even years to resolve.

Mainstream medical authorities have acknowledged that they don’t know what’s happening with these people. One—very controversial, and as yet unproven—theory is that sufferers might have a persistent infection that is not responding to antibiotics. Equally controversial are the many doctors believe that patients with post-treatment symptoms are not actually suffering from Lyme disease, but something else entirely.

But there are other theories as well, such as the possibility that a long infection can lead to persistent inflammation, or auto-immune disorders.

Given the years of unreliable tests, the many years it took to discover the cause of Lyme Disease, and the mistakes that were made along the way, an understandable thicket of distrust has crept over Lyme disease.

The Dearborn Criteria is backed by the best science, but critics of the test have a point, too: that the best science still isn’t 100%. There is no perfect test for Lyme disease, and Post-Treatment Lyme Syndrome is real.

This is the sort of place where people are liable to be confused and desperate and angry. The perfect place for someone to step in and offer solutions that seem a little too good to be true - that’s in episode 5.

SCIENCE EXTRA

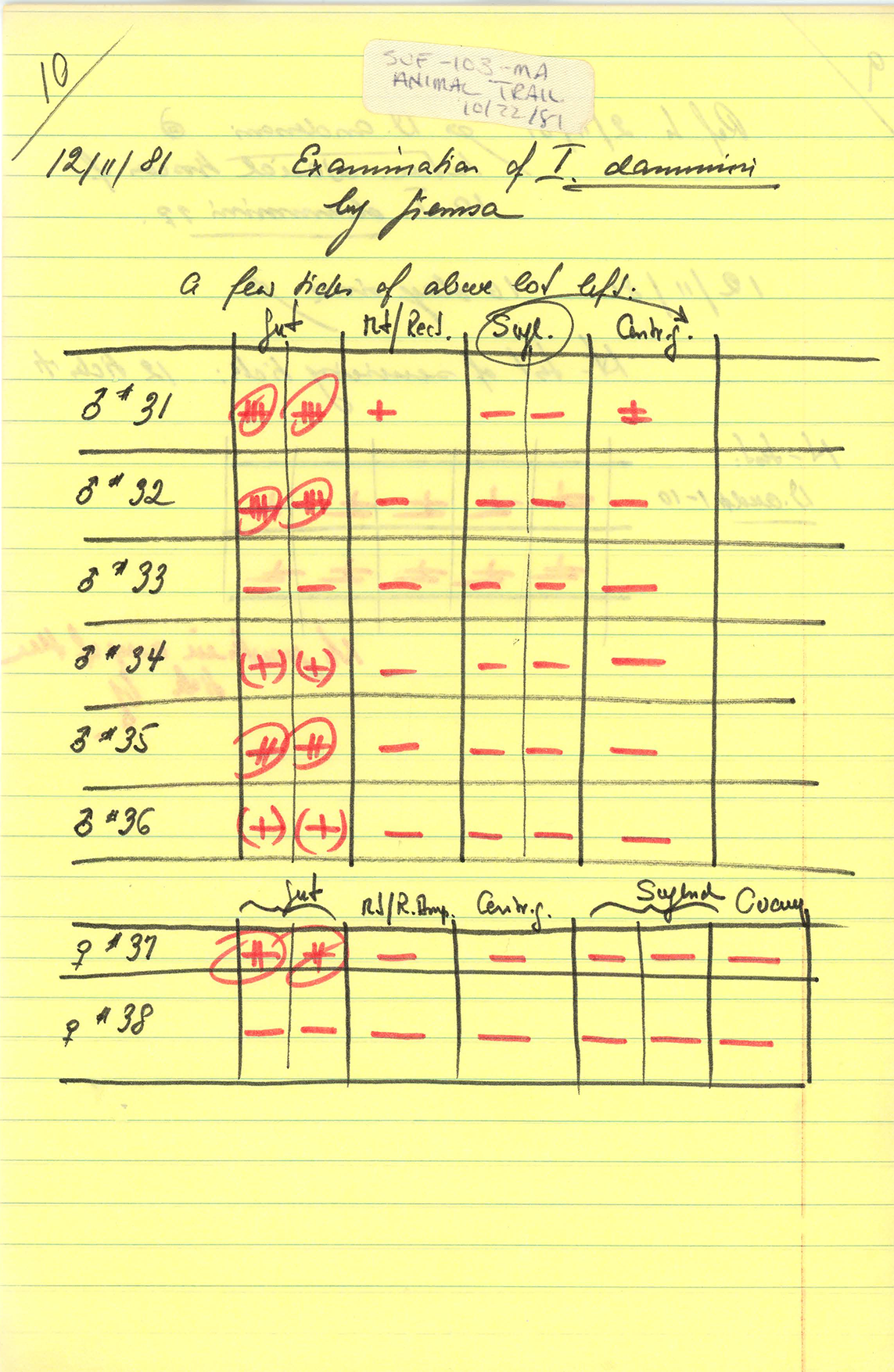

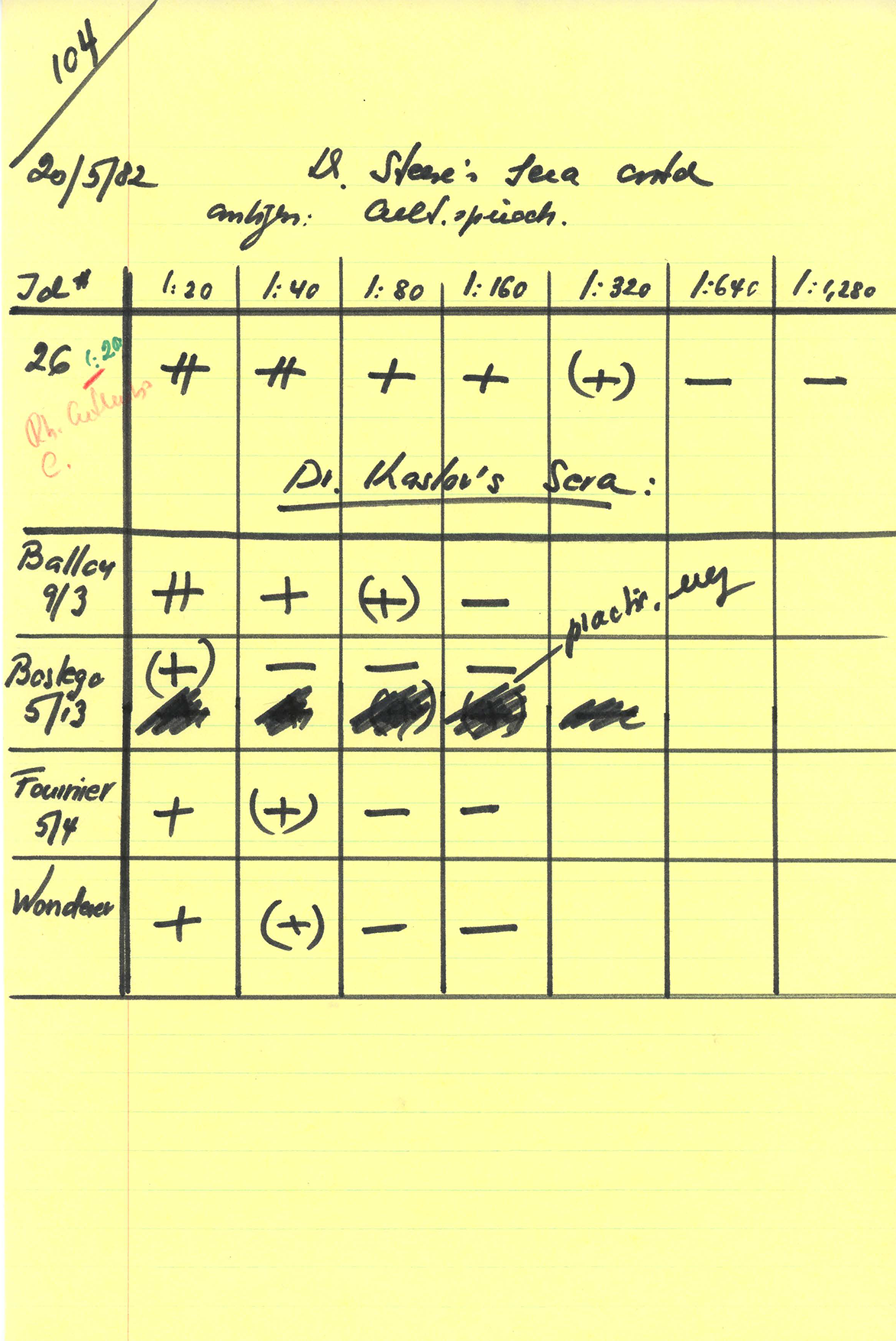

Willy Burgdorfer’s archive of Lyme-related research and correspondence is available in the public domain, and the producers of Patient Zero found it to be a rich trove of primary sources, test results, and original research notes. It is also a trove of Dr. Burgdorfer’s inscrutable handwriting. See below.